Life in the Tenth NY

- Muster in

- "The rough school of war"

- Leadership

- Picket duty and hard campaigns

- Foraging

- Simple pleasures

- Home again?

New York was the first state to supply volunteer cavalry regiments to the Union Army, in 1861. The 10th NY was one of these early regiments. The Tenth was (for its time) a relatively diverse regiment. Troopers of English and Scots-Irish descent comprised the greatest number, followed by German-Americans. One company, Company C, was almost half German and was recruited by German-born Capt. John Ordner. Irish, Scots, Welsh, Dutch, and French-American troopers rounded out the picture.

New York was the first state to supply volunteer cavalry regiments to the Union Army, in 1861. The 10th NY was one of these early regiments. The Tenth was (for its time) a relatively diverse regiment. Troopers of English and Scots-Irish descent comprised the greatest number, followed by German-Americans. One company, Company C, was almost half German and was recruited by German-born Capt. John Ordner. Irish, Scots, Welsh, Dutch, and French-American troopers rounded out the picture.

Company “F” had the distinction of being the most ethnically mixed company, with all of these groups represented. They were also the rowdiest, and in tongue-and cheek fashion they were dubbed the “Pet Lambs.” Their officer, Capt. Paige, took it upon himself to instill discipline into his unruly charges, and they became, reportedly, the most soldierly and well-drilled company in the regiment.

Camp life in the Tenth is summed up well in this letter from Guy Wynkoop:

“Camp Patterson - Park – Baltimore, July 21st 1862

My Dear Cousin Louise:

. . . I have got so accustomed to camp life, that it seems to me as if every one knew all about it - But I will tell you the main features - so that you can form some sort of an opinion as to how we live and what we do. In the first place we do everything by sound of the bugle - At sunrise the bugle sounds for roll call - we then have to get up and get into line immediately to answer to our names - if we happen to be absent from roll call at any time either at night or morning without having been previously excused - we get put on guard - one day extra duty - After roll call we have a drill of an hours duration - then comes breakfast - each Co. is divide into four messes - and each mess cooks for itself - we have a man detailed for the purpose of cooking and he is excused from all other duties - When we were in Havre de Grace there were five or six of us in a mess and we took turns in cooking - I got along well enough - but I didn't like the business - However we never have lived better since we left home than we did then - but I am getting off from my story - to return - After breakfast comes the sick call when the Orderly Sergt. of each Co. has to report to the Surgeon all men who are unwell - at 9 o'clock is guard Mounting - Of course none but those who are detailed each day have to appear at guard Mounting - well at ten o'clock the commissioned officers have a drill and at 2 P.M. the non-commissioned officers - of course we have dinner at noon - Well then we have nothing else until most sun down when we have Dress Parade; we have supper either before or after Dress Parade just as we see fit - at 9 P.M. we have roll call which winds up the programme.

At present we are not drilling a great deal - We expect our horses soon, and then I suppose they will put us through - It is expected that we will be sent to Annapolis Junction as soon as we are mounted.

We are living in tents of course. Sergt. Binnell and myself have one by ourselves and we live as cosy as you can imagine - Our camp is situated in a splendid grove just outside of the City - within ten minutes walk of Fort Marshall - I assure you the shade has been very acceptable, as it has been awful hot - some days as high as 100º in the shade. . . .”

The average age of the enlisted men was 25, with the largest single age group being 18-year-olds. The officers called them their “boys,” and mostly, they were. However, there were also men in their thirties and forties among the enlistees, and fifties among the officers. Many of the men worked on their families’ small farms before the war, but many other professions were represented, such as lawyer, minister, student, dentist, bookseller, sign painter, and so on. Judging from their letters home, some of the enlisted men were very well educated, while others could barely read and write.

The average age of the enlisted men was 25, with the largest single age group being 18-year-olds. The officers called them their “boys,” and mostly, they were. However, there were also men in their thirties and forties among the enlistees, and fifties among the officers. Many of the men worked on their families’ small farms before the war, but many other professions were represented, such as lawyer, minister, student, dentist, bookseller, sign painter, and so on. Judging from their letters home, some of the enlisted men were very well educated, while others could barely read and write.

Like many of their compatriots, the men of the Tenth were attracted by the glamour of cavalry service, but were often woefully lacking in riding skills when they joined up. If other Yankee regiments are any guide, perhaps 75% of Tenth New Yorkers did not know how to ride a horse when they enlisted. They were not issued horses until August and September 1862, just before going on campaign. (The officers, who had supplied their own horses, had been mounted far longer.) Many of the horses were green-broke or even unbroke, compounding the troopers’ difficulties. Capt. Vanderbilt, who commanded Company L (one of the last companies to be recruited), recalled that his men received horses and saddles only a month before going on the march. In December, Company L, along with 2 companies of the 6th Pennsylvania, was detailed as an escort to Major General William F. Smith, 6th Corps, enroute to Fredericksburg. (The rest of the 10th was under Bayard’s Cavalry Brigade at the time.) The novices overpacked their horses with everything from extra quilts to folding patent stoves. When General Smith took off down the road at a gallop expecting his escort to follow, an impromptu “rodeo” ensued. Captain Vanderbilt, in command of Company L, wrote:

“Such a shouting, scrabbling and cursing you never heard . . . Some horses reared or stood up like trained circus ponies . . . ‘Cloose up,’ I yelled, but of course they couldn’t close . . . Poor boys! Their eyes popped out like those of maniacs. They didn’t all get up until noon.”

Like many volunteers in the Union cavalry, the Tenth’s enlisted men developed their riding skills in “the rough school of war” rather than by formal instruction.

The Tenth’s officers, too, paint a picture that was all too common in the Union’s volunteer regiments. The military “schooling” of many of the Tenth’s officers consisted of reading manuals on drill and tactics while encamped at Gettysburg in early 1862. This task they applied themselves diligently to, but the soon discovered that the reality of war was very different from the books. Like the enlisted men, they too had to learn on the job. Over time, the unfit were weeded out and the best rose to the top, often from the enlisted ranks. Some, like Syracuse bookseller Matthew Henry Avery, were natural leaders, and rose to the occasion.

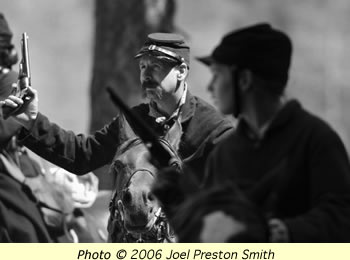

The Tenth contained its heroes and its scoundrels. Contrast the behavior of the Tenth’s first commanding officer, Colonel Lemmon (below), with that of its second, Lt. Col. Irvine. Colonel Irvine had only recently returned from sick leave when the Tenth was called to fight at Brandy Station, the greatest cavalry battle of the Civil War. Major Matthew Avery recalled:

“I never saw so striking an example of devotion to duty. He rode into them slashing his saber in a measured and determined manner just as he went about everything else, with deliberation and firmness of purpose. I never saw a man so cool under such circumstances.”

In the ensuing melee, Irvine’s horse fell with him, and he found himself wounded and surrounded by Confederates. He spent 4 months in Libby Prison until he was exchanged. His health broken, he never again saw active service, although he campaigned on behalf of soldiers in Confederate prisons.

In his article “The Union Cavalry at Gettysburg,” Major General David McMurtrie Gregg wrote:

“In some instances, the colonels were aged men of local influence, whose patriotic zeal, associated with an imagined dash of character, led them to enter an arm of service, the fatigues and hardships of which compelled an early return to their homes; in others, they were men who had been selected for any other reason than even their supposed fitness to command, and these, by their incapacity or unwillingness to learn their duties, fell under the contempt of their commanders.”

General Gregg might well have been describing Colonel John Lemmon, the first commander of the 10th NY. Although well respected in private life, where he made an excellent living in the milling business, he proved to be a political manipulator in the Army. In April 1863, while recuperating from a leg injury (see below) he launched a “coup” that decimated his officer corps by bringing fabricated charges against them. Other officers resigned in protest. Coming just before the difficult campaigning of 1863, this was a devastating loss. Some of the officers Lemmon targeted, like Capt. Wilkinson Paige and Capt. John Ordner, were those best liked by the men.

But Lemmon himself was not to last long. In On October 11, 1862, a surprise raid by the Confederates had found Lemmon riding in the ambulance in the rear of the column (his habitual station). Fearing capture, Lemmon ordered the hospital steward to exchange jackets with him. The ambulance was upset and Lemmon dislocated his knee. Lemmon’s cowardice eventually came to the attention of his superiors, and he was not allowed to rejoin the 10th. Later in 1863 and early in 1864, most of the dismissed officers were reinstated. Still, Lemmon kept up a letter writing campaign against them, and his letters even reached the desk of President Lincoln. Lemmon’s appeals failed to change Lincoln’s mind, and several of the reinstated officers later distinguished themselves in battle or were killed in action while leading their men. The litany of officers killed or wounded in the Tenth from 1863 on is striking, attesting to the fact that those who stayed on fought with their men rather than keeping safely to the rear. Doubtless their bravery helped to strengthen the resolve of tired and homesick troopers as the war dragged on.

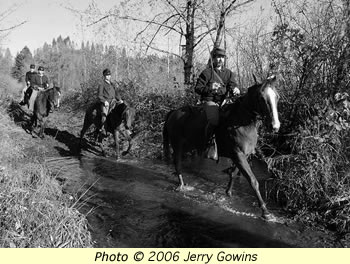

The Tenth was, in many ways, a microcosm of the experience of Union volunteer cavalry during the Civil War. Early in the war they performed guard and picket duty at the bridges and other crossings of the Susquehanna River. After Sept. 1862, they campaigned actively. But until the spring of 1863, when the cavalry was reorganized, their strength was squandered on long marches, or divided up amongst various assignments. General Gregg summed up the situation well when he wrote:

The Tenth was, in many ways, a microcosm of the experience of Union volunteer cavalry during the Civil War. Early in the war they performed guard and picket duty at the bridges and other crossings of the Susquehanna River. After Sept. 1862, they campaigned actively. But until the spring of 1863, when the cavalry was reorganized, their strength was squandered on long marches, or divided up amongst various assignments. General Gregg summed up the situation well when he wrote:

“ . . . for, while it was the fashion to sneer at the cavalry, there was a remarkable fondness displayed at corps, division, and brigade headquarters of infantry for the presence of numerous and well-mounted orderlies; details for this ornamental and often menial duty, and those for the most grossly absurd picket and escort duty, absorbed pretty much the entire cavalry.”

Cavalry units often saw more action than the infantry did, although many of the fights were on a smaller scale. In fact the Tenth was involved in more than 150 battles, skirmishes, and raids over the course of the war. (More than 60 of these were regular engagements where artillery was used.) Despite the opinion prevalent among infantrymen that cavalrymen enjoyed a relatively easy life, they were often exposed to great hardships. In the winter, while most infantry were ensconced in their winter camps, the 10th New Yorkers performed picket and scout duty. In his book One of the People, Burton Porter recalled the winter of 1862-3:

Cavalry units often saw more action than the infantry did, although many of the fights were on a smaller scale. In fact the Tenth was involved in more than 150 battles, skirmishes, and raids over the course of the war. (More than 60 of these were regular engagements where artillery was used.) Despite the opinion prevalent among infantrymen that cavalrymen enjoyed a relatively easy life, they were often exposed to great hardships. In the winter, while most infantry were ensconced in their winter camps, the 10th New Yorkers performed picket and scout duty. In his book One of the People, Burton Porter recalled the winter of 1862-3:

“On the 6th [January, 1863] the whole regiment was ordered on picket between the Potomac and the Rappahannock . . . On January 20th our company was on picket near Muddy Creek . . . A terrible storm raged all the while we were out . . . [on the 28th] the whole regiment was ordered out on scout during a heavy snow storm which continued until the snow was six inches deep. We camped that night in a piece of woods and I lay on two rails to keep out of the mud and water.”

In the infamous Stoneman raid in the spring of 1863, the Tenth covered 600 miles in ten days. They slept no more than two hours at a time on this march. As horses gave out, the men simply saddled a new one from the herd of captured horses, and kept going. Those who could not find a suitable mount were left behind to the tender mercies of the rebels.

On the other hand, in the summer, dust was the constant companion of the cavalryman. In a letter written from Centerville, VA on June 16, 1863, Guy Wynkoop wrote:

“We have had no rain. Not so much as a good shower since the 10th of May and everything is drying up - The ground is as dry as an ash heap and dust is a staple comodity - You can have no idea of the dust that a Column of Cavalry will raise in marching - It is as much worse than a threshing machine & as that is worse than a sleigh ride, when there is capital sleighing - So you may know that it is not altogether pleasant . . .”

“Foraging” was a constant theme in the cavalryman’s existence, but the men were instructed to treat civilians fairly, and pay them (or give them official receipts) for food and supplies taken. In the fall of 1862, a minor furor erupted when angry citizens came to Lt. Col. Irvine accusing his men of raiding local farms. Col. Judson Kilpatrick, then leading the 2nd NY, sneeringly called the Tenth “an aggregation of chicken thieves.” The miscreants had been identified, the civilians said, by the brass “10s” on their caps. Irvine immediately ordered all of his men to remove their hat brass, and they went in search of the thieves. Sure enough, they rounded up a number of fellows wearing “10s” —and loaded down with farm products—but these were all members of the 2nd NY, who had altered their hats so that the 10th would be blamed. They were returned to Kilpatrick, who feigned outrage, but let the men go without punishment.

But not all foraging expeditions were so innocent, especially when hunger intervened, as this letter from Manning Austin of Company G attests:

Letter datelined Harewood (Md), Aug. 8, 1864:

“I must tell you about my jayhawking last night....I went out and confiscated some of an old secesh’ ducks to my own special benefit. When we had the order to be ready to march, they stopped our rations so that we had nothing but bread & coffee & musty old rice to eat....I had never been in the habit of asking for what few apples I wanted to eat while passing through an orchard in York state...thought I should not commence it by asking then of an old secesh who deserved to have a rope around his neck....he then came down to the beach where we then were...saying that we were a pack of villians...I told him if he did not look out...we would string him up to a tree and leave him to breath his last. One of our boys...was going to kill him...slapped his face....When a rebel won’t sell me anything to eat when I need it, I will help myself....some of our boys have gone out tonight to search a house for a rebel flag and clothing that they have been making for the southern army...the secesh are as thick as fleas on a dog....”

Raiding was also a constant feature of the cavalryman’s life. Raids conducted by cavalry to disrupt Confederate lines of supply and communication became more frequent in 1864, when the Army under General Grant pursued a “total war” strategy. A letter from Pvt. Justus Matteson tells of a typical raid:

Raiding was also a constant feature of the cavalryman’s life. Raids conducted by cavalry to disrupt Confederate lines of supply and communication became more frequent in 1864, when the Army under General Grant pursued a “total war” strategy. A letter from Pvt. Justus Matteson tells of a typical raid:

"Dec 1st our division went on a requinoisance to Stoney Creek. we started at 4 in the A.M. drove in the reb pickets about day light. we struck the RR at Duvals station, destroyed the station, a steem saw mill, barell factory, stone houses, one train of cars, tore up some distance of the track, got 7 or 8 wagons and trains. allso took 4 pieces of artillery, spiked them, and rolled some of them into a pond. could not get them off for the want of teams. took 187 prisoners in the scrape. our reg't had one man killed, one mortaly wounded, and eight severly. two of the latter wer of our co. one Corporeal John G. Hicks of Cortland. they wer both wounded in the arm. Daniel Ansinger of our Co had his hat shot off. I had a hole through my sleeve.”

Pvt. Matteson’s letters to his sweetheart at home also tell of the conditions the men of the Tenth endured:

“we had a tedious march to Gettysburg . . . my horse played out so I was dismounted and had to go behind with the mule train.” (July 10, 1863)

“I have just drawn my rations. they are the first that I have got in two weeks.” (July 10, 1863).

“I was in the cav fight at Sulphur Springs. my horse was shot and I had to walk here a distance of fifty miles and was sick with the ague [malaria] at the time. it was the hardest time that I seen yet . . .” (Dec. 3, 1863)

“ . . . we have been on the move amost every day since. Our Cav fought the rebs for nine days running.” (May 22, 1864, after Sheridan’s Richmond raid)

“We have just returned from a raid of over two weeks. I have been in three hard Cav fights since I wrote last and under shelling five or six times besides . . . there is scarcley a day passes but some one of the regt is sun stroke. I came near it several times.” (June 27, 1864, after the Trevilian raid)

“we have scarcley had the saddles off of our horses in three weeks” (Aug. 30, 1864)

“You wanted to know how I spent Thanksgiving. well I worked all day hard making us a tent. of those good things that wer sent to us, we recieved but little of. I got 1 1/2 apples and half of a turkeys leg. the officers had the first handling of them and took the lions share.” (Dec. 4, 1864)

But there were moments where the soldiers enjoyed simple pleasures, as well:

“It is a beautiful night and Oh, how I wish you wer here to hear the music. there ar several brass bands playing close by, and it is delightfull to hear them” (Dec. 4, 1864)

“Mary, I think I’ve got the start of you getting strawberies & cheries this season for I went out about a week ago and got all I could eat . . .” (May 25, 1865)

After the war was over, some of the Tenth New Yorkers returned to the places of their birth, to settle down and raise their families. Others scattered to the winds, seeking new opportunities the rebuilding nation offered. A substantial contingent settled in Michigan, while others went as far as Missouri, Texas, and even the West Coast. One veteran, Aaron Bliss, became a governor of Michigan; Truman White became a respected judge who presided over the trial of the assassin of President McKinley; and Dr. Walter Kempster did pioneering research into the physical basis of mental illness.

Some men never fully recovered from their physical and psychological wounds. At least one veteran of the Tenth committed suicide—supposedly caused by drinking too much ice water--and many suffered lifelong effects of wounds, starvation in prison camps, or diseases incurred during their cavalry service. Many of the less well-to-do ended their days in old soldiers’ homes.

After the war, as before, the men and boys of the Tenth were a microcosm of American life, but they had been forever changed by their experiences.

References

Austin, Manning, Company G, 10th N.Y. Cavalry. 16 letters dated March 1862-November 1864. Posted online at: David G. Phillips Co., Inc. Sale #106, United States & Foreign Covers & Postal History, January 27, 2001. http://www.stampauctioncentral.com/c/c1061.htm

Gregg, Major-General David McMurtrie. “The Union Cavalry at Gettysburg.” In: Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, editors, 1887.

Lincoln, Abraham. Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Edwin M. Stanton, Thursday, October 22, 1863 (Orders reinvestigation of cases of dismissed officers in the 10th New York Cavalry.) In: Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mal:@field(DOCID+@lit(d2738400))

Martin, Samuel J. Kill-Cavalry: The Life of Union General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick.

Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000.

Matteson, Ronald G., Justus in the Civil War, Letters from a private in Co. L, 10th NY Vol. Cav., 138 pages, Walworth, NY: self-published, 1995.

Porter, Burton B. One of the People: His Own Story. Colton, CA: self-published, 1907.

Preston, Noble Delance. History of the Tenth Regiment of Cavalry, New York State Volunteers, August, 1861, to August, 1865, by N. D. Preston, with an introduction by Gen. David McM. Gregg. Published by the Tenth New York Cavalry Association. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1892.

Rummell III, George A. 72 Days at Gettsyburg: Organization of the Tenth Regiment, New York Volunteer Cavalry. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane, 1997.

Wynkoop, Guy, "Wynkoop, Guy; 10th N.Y. Cavalry, Co. H., Letters (1862-1863), 2 items," New York State Library, Cultural Education Center, Albany, New York, New York State Library Manuscripts and Special Collections, Collection Call Number: 19402, [8 pages]. Posted on:

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~wynkoop/webdocs/guywkp.htm

Copyright Christopher H. Wynkoop, 2002-3.